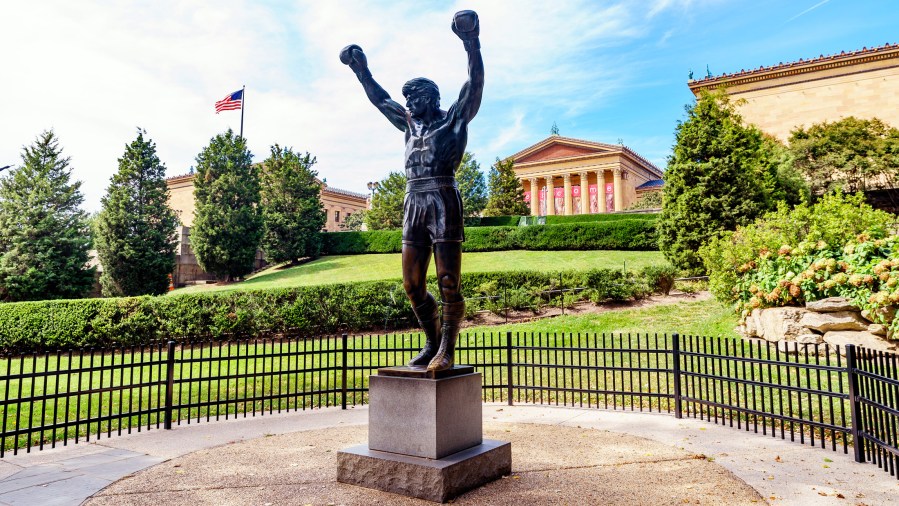

Philadelphia is the City of Brotherly Love. It also is a place ripe with stereotypes, from Rocky Balboa running up the steps of the Philadelphia Art Museum to the late comic David Brenner making jokes about growing up in Philadelhia’s edgier neighborhoods. (“Fabbio are you from Philadelphia, too?” he once said, quickly following it up with, “Did you steal my bike?”)

In 2006 writer Steve DiMeo, who I had the pleasure of working with at an advertising and public relations agency in Philadelphia, put pen to paper to re-imagine the holiday classic “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” What follows is his wonderful rendition of the holiday favorite.

Christmas in South Philly

A Visit From Uncle Nick

or, “’Twas? What da hell kinda word is ‘Twas?”

By Steve DiMeo

‘Twas da night before Christmas,

You hear what I’m sayin’?

And all through South Philly,

Sinatra’s Christmas tunes was playin’.

Da sink was piled high,

Fulla dirty dishes,

From da big Italian meal

Of gravy and seven fishes.

Da brats were outta hand

From eatin’ too much candy.

We told them to go to bed

Or there wouldn’t be no Santy.

And me in my sweatpants,

Da wife’s hair fulla rollers,

Plopped our butts on the sofa

To fight over remote controllers.

When out in da shtreet,

There was all dis friggin’ noise.

It sounded like a mob hit,

Ya’ know, by Gambino and his boys.

I trew open da stormdoor

To look and see who’s who.

Like a nosy little old lady

Who’s got nuttin’ better to do.

In da windows of da rowhomes

Stood white tinsel trees.

And those stupid moving dolls

You get on sale at Kindy’s.

When what should I see,

Comin’ from afar.

But fat Uncle Nick

In his big ole Towne Car.

He was swervin’ and cursin’,

Givin’ all da gas he got;

As he barreled up the shtreet,

Looking for a spot.

More faster than Santa,

My drunk Uncle came;

Wit’ a car full of relatives,

All drunk just the same.

“Yo Angie! Ay Dino!

Vic, Gina, and Pete,”

He yelled out there names,

Then spit a loogee in da shtreet

“I can’t find no spot nowheres,”

Pissed off, he said.

So he double-parked the Lincoln,

And came in to hit da head.

As he hugged me, he burped,

And passed a loada gas.

It stunk up da house,

Like a rotten sea bass.

His coat was pure cashmere,

His pinky ring shined;

His toupee was all twisted,

The front was now behind.

He ran up to da bathroom,

Bangin’ pictures wit’ his hips.

Never lettin’ da smelly stogie

Fall from his lips.

With eyes oh so bloodshot,

And a butt, oh so flabby;

In walked Aunt Angie,

All dolled-up and crabby.

“D’jeat yet?” she asked,

As she thundered to da kitchen;

“All da calamari’s gone?”

Aunt Angie started bitchin’.

In came Cousin Gina,

In Guess jeans too tight.

She was bathed in Obsession,

Her hair reached new height.

In strut Cousins Dino,

Little Petey and Big Vic;

Shovin’ pizzelles down their throats,

It was makin’ me sick.

I said, “How da hell

Are all youse people doin?”

Not one of them answered,

They was too busy chewin’.

Uncle Nick came down at last.

His face was beet red.

“Sorry I missed da toilet.

I pissed in the bathtub instead.”

That was it, I had had it.

I yelled, “Get the hell out.”

Uncle Nick looked real puzzled.

Cousin Gina started to pout.

Wit’ that they mumbled curses,

And opened a Strawbridge’s bag.

And fumbled ‘round to find da gift

Wit’ our name on da tag.

I then felt kinda stupid,

As I thanked them for their gift.

But they stormed out da stormdoor,

All of them miffed.

We tore open da paper

That was taped on and on.

It was a bottle of Sambuca,

And half of it was gone.

But I heard him yelling

As he slammed on da gas.

“Merry Christmas, ya ingrate!

You can kiss my ass!”

Yo. Happy Holidays, a’ight?

© 2006 by Steve DiMeo